Mining the depths of cobwebbed shelves in a second-hand bookshop, hunting—as ever—for

lesser known poets that might offer me a gateway to Being, I come upon an anthology of Sylvia

Plath’s poetry. I almost pass straight by.

After all, she’s not known as a ‘sacred poet’. She’s also become something of cliché: a tortured

young writer who took her own life. (She left bread and milk in the rooms of her two infant children

and sealed around their doors to keep them safe from the gas. She then made a pillow in the oven

and laid her head upon it.) Do I really want to enter her pained world?

But today, I do open the book and my eye falls upon the poem ‘Ariel’. It was written three months

before her death, on her birthday, in 1962. I hesitate. And then I read.

Stasis in darkness.

The poem begins in stillness; end-stopped to slow us down and emphasise the internal rhyme and

slant rhyme.

Then the substanceless blue

Pour of tor and distances.

The narrator, atop her horse Ariel, sets off hurtling through the landscape. Enjamberment (lines

that run on) speeds her words.

God’s lioness,

How one we grow

The boundary between her and the horse is dissolving...

Pivot of heels and knees!—The furrow

Splits and passes, sister to

The brown arc

Of the neck I cannot catch,

But the process is interrupted as she can’t get a hold of the horse…

Nigger-eye

Berries cast dark

Hooks—

Black sweet blood mouthfuls,

A jerk backwards: the world of sensory experience catches her and delineates her small self again.

Shadows.

And then,

Something else

Hauls me through air—

Now, the seeming solidity of the world becomes less concrete; it begins to be felt—a taste of the

oneness she yearns for. She is being called back. She struggles to find words for it.

Thighs, hair;

Flakes from my heels.

The boundary between the narrator and her body starts loosening. She sheds her physical form.

White

Godiva, I unpeel—

Dead hands, dead stringencies.

She sheds her memories and responsibilities, until she feels herself to be the 11th century Lady

Godiva who, naked upon her horse, rode through the crowds. Here too is the colour opposite of

those black, hooking berries.

And now I

Foam to wheat, a glitter of seas.

The boundary between herself and world breaks up. She takes a step closer to the dissolution of

subject-object as she becomes the powerful verbs, the movement.

The child’s cry

Melts in the wall.

Now she sheds too her children (they were aged three and one when she wrote this) and/or her

internal child,

And I

Am the arrow,

The dew that flies

Suicidal, at one with the drive

Into the red

Eye, the cauldron of morning.

And, the finale. After black and white, comes red. She becomes one with all.

I take the book down: beautiful! Contextually, we know that Sylvia often sought to be free of her

suffering through riding. Here she’s liberating herself through the act of writing about her narrator

on horseback. And she’s taken me there too.

But, if that’s the case, why then, not that long afterwards, did she kill herself? Since childhood

she’d idealised ‘eternal oblivion’ as a solution to her anguish. In the end, it won out. Is that the

action of someone who knows their true nature?

Sylvia’s sense of a separate self spent its whole short life trying to write its way to freedom. (Her

use of the name Ariel in this poem not only alludes to her horse, but also to the air-spirit Ariel in

Shakespeare’s The Tempest. For him, freedom from servitude came at the end of the play.)

Word-crafting did a good job; it saved her life many times. I imagine each of her poems of as an

island of safety she managed to swim to. The fact that she lived another three months after writing

‘Ariel’ was a huge success rather than a failure; she was someone who’d fought suicidal despair

for most of her life. (Today, the western mental health system would almost certainly label her as a

sufferer of Bipolar Disorder.)

My sense is that Sylvia had glimpses of, windows on to, her vast, limitless self, but that she could

never stay there. The reason she could never stay there was because she attributed those

moments of relief to the act of writing—to the objects that are those small ink marks on the page.

As a writer I know only too well how it can go: In an effort to get outside of duality, of concepts, we

can, ironically, just spend our lives banging our heads against them. The problem with words is

that we can only ever write about what’s inside them, so to speak. The more Plath described the

perceived sources of emotional pain, recorded her racing, dark thoughts and fantasised about

death, the more she embedded those narratives. In that situation, we’re all in danger of feeling

increasingly overwhelmed by the material. We can come to believe that we are fragile and the

content of our minds will shatter us. We forget who we truly are.

But peace and freedom exist outside of the tiny scratchings on the page; the words are just the

finger pointing at the moon. In Plath’s final stanzas, Being is found in the white space that opens

between the ‘I’, that portal to her true nature, and ‘am the arrow’. It’s also in the line breaks.

And I

Am the arrow,

The dew that flies

Suicidal, at one with the drive

Into the red

Eye, the cauldron of morning.

To know this I only have to go to my own experience: as the words give themselves up, it’s in the

hush. As you too read these final stanzas, don’t you feel it?

What Sylvia yearned for, above all else, was hiding in plain sight all along; the lifeboat was in the

gaps. And not only in the gaps. Ultimately, the ink marks are not separate from the page; there are

not two things. However, to know their true nature, I must first comprehend their transparency.

Suddenly, I feel terribly sad for Sylvia Plath. God was, in fact, always with her and always calling

her back to itself. She didn’t need to strive to know it’s presence. She didn’t need to get to

anywhere else—not to being a different or ‘better’ person, not to the end of the narrative arc and,

certainly, not to death. Sylvia always was, and remains, only the page itself, as we all are.

And then, suddenly, I experience something akin to the Aha! moment of the haiku poets. I know

what I need to do: I must save Sylvia’s life.

I would liberate her, restore her to herself, line by line. She doesn’t need to stay stuck in the story.

It’s not necessary to begin with act 1. She can open in the space after the final line of act 3—the

finale—and then stay there.

It was a strange idea and obviously not accurate, on a relative level, as she ended her life sixty

years ago. But, as she lives on through her words and as her true self is unending, I knew it to be

exactly right, in absolute terms.

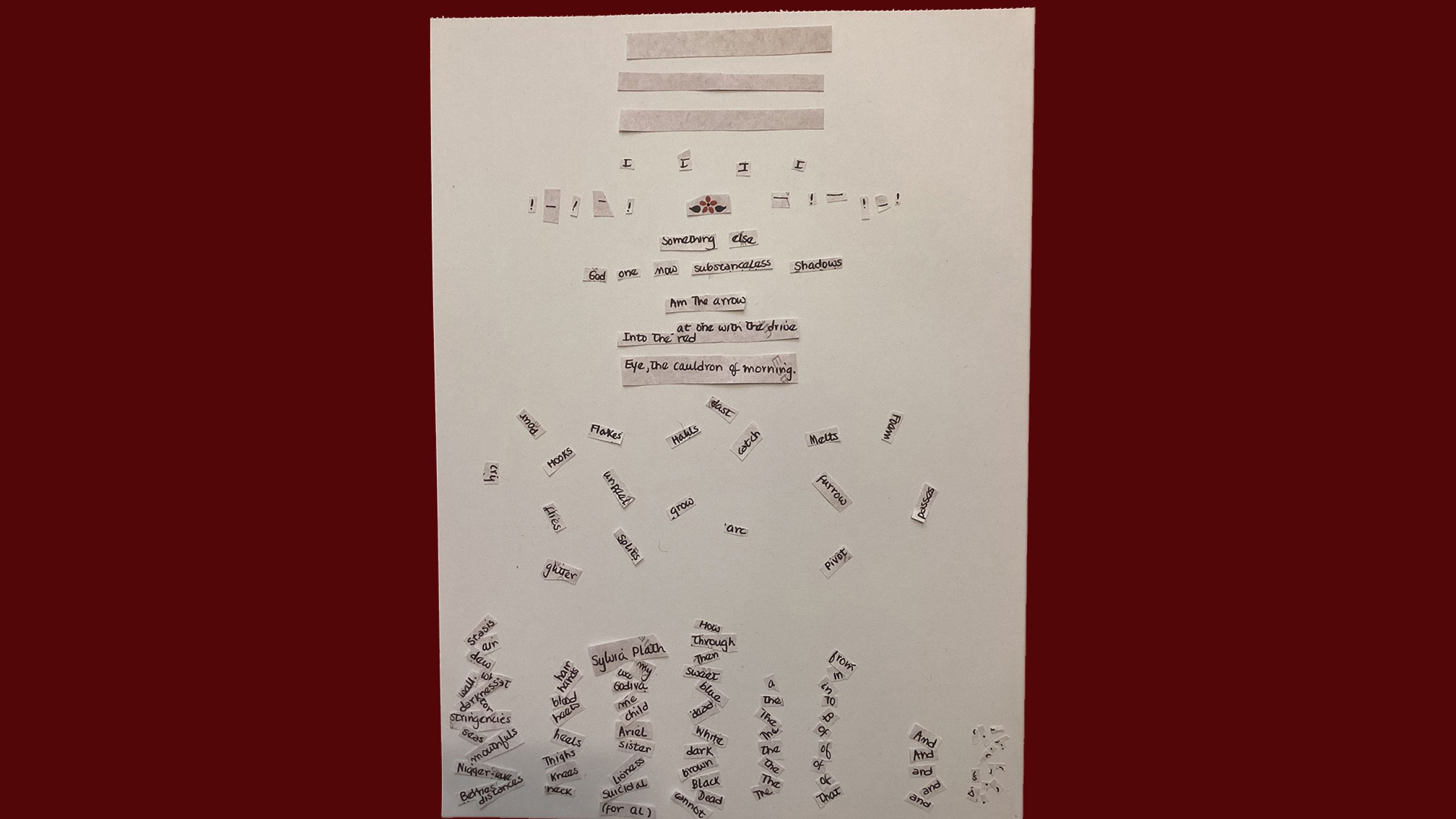

So, this is what I did:

I printed out a copy of her handwritten manuscript of ‘Ariel’. I cut it into pieces–both the individual

words and the spaces in between. Then I got out the glue.

First would come the white space. I was thrown, for a moment, by the limitations of the medium.

How could I show an absence of time and space when I had to place even Ariel’s gaps within the

space of the paper?

I let myself rest in the wordlessness around the words.

In doing so, I remembered my Self. And then this is where my hands were led.

I placed, at the top of the page, her white spaces.

Next came her personal pronouns: I reclaimed ‘I’ from her misunderstanding of what ‘I’ is to stand

as the portal to the divine. I. I. I.

And punctuation: the pauses of the em-dash — — —. The moment of awe of the exclamation

mark: !

Then came the words next closest to wordlessness: Something else. Now. One. God.

Holding and placing each tiny, hand-crafted word written, I was struck by the power and the

poignancy. There were the quirks of her hand and the places she corrected her script. I was

touched by the dedication she offered and the flower she drew.

Now, I laid down her metaphors from the final stanzas. These were the places where she got so

close in words…

Am the arrow,

at one with the drive

Into the red

Eye, the cauldron of morning.

Then, something very beautiful happened with her words denoting movement—her verbs: they

began to free float in the space. Pour. Flakes. unpeel. Melts. Foam. Catch. cast. Pivot. Splits.

Hauls. grow. passes. More wonderfully still, some nouns lost their subject-object relations and

joined the family of verbs! furrow. arc. Hooks. glitter. cry.

Sylvia no longer has to feel it is she that hauls or is hooked. There is no-one to whom these things

happen. They are revealed to be a dream sequence arising without volition.

I looked then at the vast array of nouns still spread out before me: all those labels around which

she formed judgements and which therefore limited or diminished her. She went some way to

dissolving her horse and her world in her self, but now I would go further. I would dispose of those

nouns! With vigour, I began to pile them up.

The parts of her body—heels, knees, thighs, hair—that, when her husband took a lover, seemed

evidence to her that she ‘wasn’t attractive’.

Her relationship to her child on two levels: her beliefs that she was a failure of a mother and that

damage was done to her as a child.

‘Sylvia Plath: suicidal poet and madwoman.’ Whilst not wishing to diminish or disrespect her very

real sense of suffering, the ways in which she herself, as well as society, have reduced her to

keywords, angered me. Her true self was, and is, so much more. She is vast and unblemished.

Now, with a sense of Sylvia on my shoulder, I was really getting into my stride. I made a bonfire of

those tricky adjectives and adverbs: then. through. I heaped up the definite articles that defined

the meaning of a noun as one particular thing—that reinforced the idea of free-standing objects:

the. And the indefinite articles likewise: a.

Next, words that misleadingly reinforced the idea of existence time or space were gone:

demonstrative pronouns: that. And prepositions: Of. To. from. in.

Pesky conjunctions (joining words of equal status that further seem to confirm the separate

existence of objects) went too: And. And. And.

I was running out of space on my canvas but I wanted to do something with those ink marks that

are the tiniest but which wield great power: punctuation marks. The apostrophe ‘s that signals that

there’s a someone who owns something; the commas and full stops that divide and sub-divide: , .

My fingers were clumsy—too big for the delicate task—and commas kept sticking to my gluey

fingers. But I got there; I found a corner for them.

I stepped back and looked at what I had done. I felt so much better, as if I’d lifted a weight from

Sylvia’s shoulders and from my own.

I saw immediately other things I wanted to do: make those physical objects of words

transparent—as intangible as the play of light; have part of the paper unfold like a shrine to a yet

vaster canvas; cut windows into the layers of a whole book to see through to what is truly true…

But they were for another time.

In the process of Saving Sylvia, I saved myself. I remembered that I am always and already free.

When I know that, I restore my joy in crafting words—in the delighted play of that freedom on the

page.